Who migrates?

Read the selection from chapter 4 of the World Migration Report 2024 ‘Growing Migration Inequality: What do the Global Data Actually Show?’ and then answer the questions.

Migration and the lottery of birth

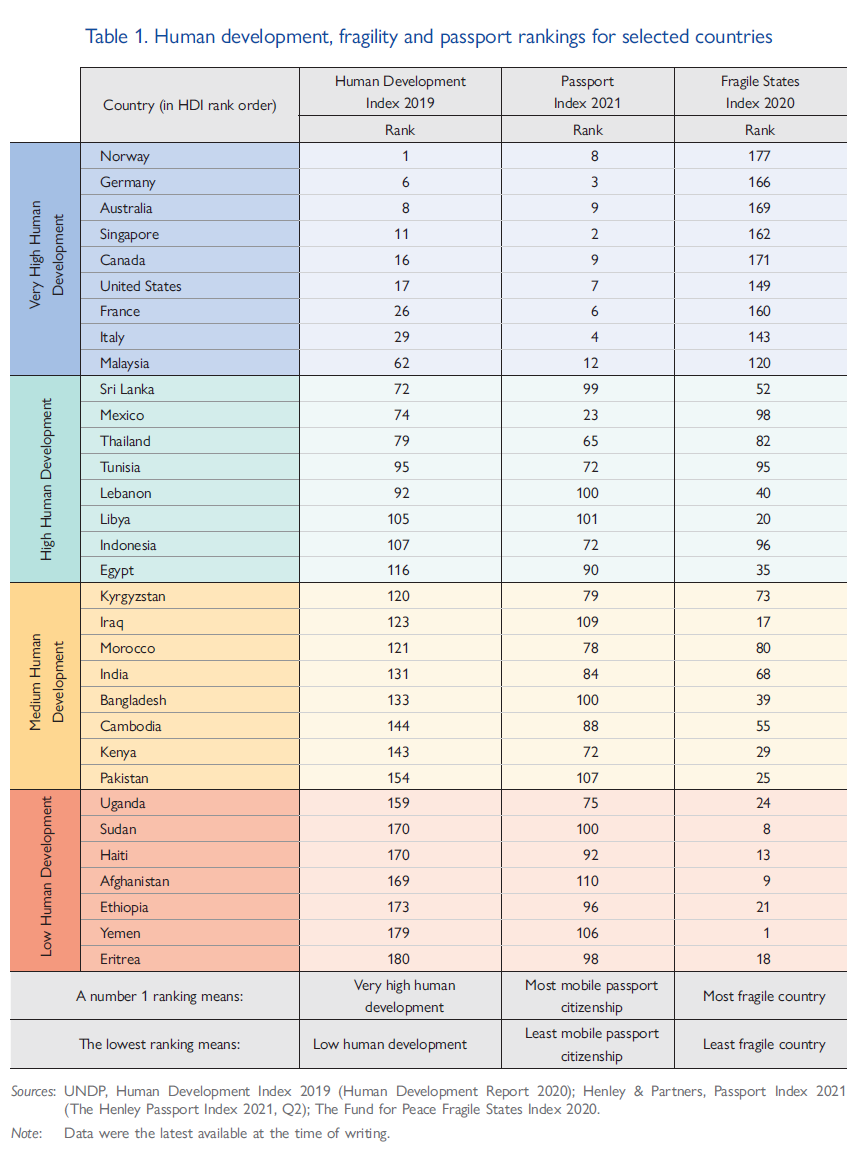

Examining the overall quality of life by country, and the ability to migrate in terms of visa access, reveals that availability of migration options is partly related to the lottery of birth and in particular the national passport of the potential migrant. For instance, some nationality groups appear to be much less likely to have access to visas and visa-free arrangements. Table 1 below summarizes global indices of human development, fragility and visa access for selected countries. The Passport Index, a global ranking of countries according to the entry freedom of their citizens reveals for example that an individual’s ability to enter a country with relative ease is in many respects determined by nationality. Entry access also broadly reflects a country’s status and relations within the international community and indicates how stable, safe and prosperous it is in relation to other countries. The data also show two other aspects: that there are some significant differences between highly ranked human development countries and others; and that mid-ranked development countries can be significant source, transit and destination countries simultaneously. Nationals from countries with very high levels of human development can travel visa free to most other countries worldwide. These countries are also significant and preferred destination countries. Toward the bottom of the table, however, the entry restrictions in place for these countries indicate that regular migration pathways are problematic for citizens. Irregular pathways are likely to be the most realistic (if not the only) option open to potential migrants from these countries. It is also important to note that low HDI countries are also much more likely to have large populations of internally displaced persons and/or to be origin countries of large numbers of refugees.

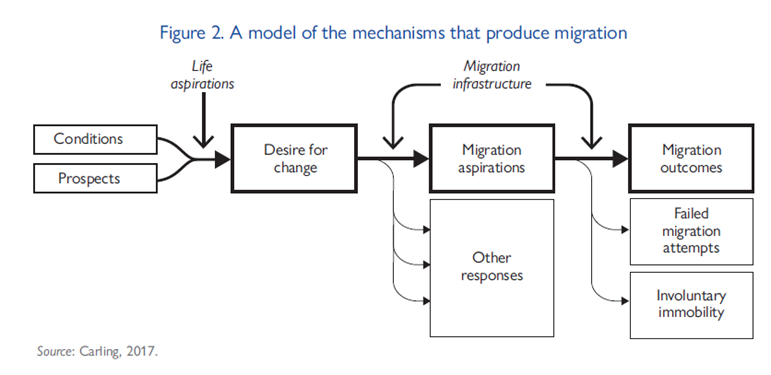

We also know, however, that nationality alone does not account for evolving migration patterns, as visa and mobility policy settings are one (albeit important) factor in explaining who migrates and where people migrate over time. Within the context of the broader discussions on migration drivers and the development of discernible migration patterns over recent years and decades, models to explain migration, as shown in Figure 2, seek to account for both structural aspects and migrants’ agency.

Importantly, this model recognizes that a desire for change does not necessarily result in a desire to migrate, and that where it does exist, a desire to migrate does not necessarily result in migration — the existence of migration infrastructure (or lack thereof) is an important factor in migration outcomes, with migration infrastructure defined as diverse human and non-human elements that enable and shape migration.

As part of this migration infrastructure, the (in)ability to access a visa can be profoundly important, not least because it is the one element that has not radically expanded over time, unlike the marked growth in “agents”, ICT, transport and connected networks. On the contrary, recent analysis shows that visa access has resulted in a bifurcation of mobility, with citizens of wealthy countries much more able to access regulated mobility regimes than those from poor countries. This is important because, wherever possible, migrants will opt to migrate through regular pathways on visas. There are stark differences between travelling on a visa and travelling unauthorized without a visa. From a migrant’s perspective, the experience can be profoundly different in a number of important ways that can impact on the migrant as well as his/her family, including those who may remain in the origin country. First, visas denote authority to enter a country and so offer a form of legitimacy when arriving in and travelling through a country. A valid visa provides a greater chance of being safeguarded against exploitation. Conversely, travelling without a visa puts people at much greater risk of being detained and deported by authorities, or exploited and abused by those offering illicit migration services, such as smugglers or traffickers, and having to operate largely outside of regulated systems. Second, travelling on visas is undoubtedly much easier logistically, as the availability of travel options is far greater. In some cases, it can mean the difference between a journey being feasible or not. Third, visas provide a greater level of certainty and confidence in the journey, which is much more likely to take place as planned, including in relation to costs.

Unsurprisingly, there is thus often a strong preference for travelling on a visa. Access to visas within decision-making contexts, therefore, features heavily in the minds of potential migrants and has been shown to be a key factor when the possibilities of migrating are explored while in the country of origin. In recent research on online job search and migration intentions, for example, the availability of visas was found to be a determining factor in how people conducted online job searches. Similarly, changes in visa settings have been found to have an impact on potential migrants’ perceptions of opportunities afforded by migration, as well as their eventual migration.

- Excerpt from WMR 2024, Ch 4.

Questions

How does the nationality of a potential migrant influence their access to visas and migration options?

In what ways do indices of human development, fragility, and visa access correlate with migration pathways and opportunities?

What are the three key differences between travelling with a visa and travelling unauthorized without a visa?

How does the desire for change relate to the desire to migrate? What factors determine whether a desire to migrate results in actual migration?