Climate change and migration

Migration and environmental change

Millions of men, women and children around the world move in anticipation or as a response to environmental stress every year. Slow-onset processes - such as sea-level rise, changes in rainfall patterns and droughts - contribute to pressures on livelihoods, and access to food and water, that can contribute to decisions to move away in search of more tenable living conditions. Disruptions such as cyclones, floods and wildfires destroy homes and assets and contribute to the displacement of people. Extreme environmental events — both attributable and non-attributable to climate change - have contributed to a rise in food insecurity worldwide. Multiple causes underpin food insecurity, including lack of food, lack of purchasing power, inadequate distribution and poor use of food at the household level. The number of people worldwide considered to be experiencing acute food insecurity and in need of urgent assistance rose to over 257 million in 2022, a 146 per cent increase since 2016. Advances in meteorological and other sciences which inform about the dynamics and pace of climate change indicate that disruptions ranging from extreme weather events to large scale changes in eco systems are occurring at apace and intensity unlike any other known period of time on Earth. In light of this increase, and the worsening impacts of climate change, there is an urgent need to assess the connections between climate change and human mobility worldwide.

Migration and slow-onset climatic changes

In the last decade, a vast amount of knowledge has been produced on the climate change and migration nexus. A recent meta-analysis of available literature concludes that “slow-onset climatic changes, in particular extremely high temperatures and drying conditions (i.e., extreme precipitation decrease or droughts), are more likely to increase migration than sudden-onset events.” Migrants moving to adapt to slow-onset impacts might have more time to gather the resources needed to migrate, while sudden-onset events reduce the ability to move by rapidly depleting resources.

Research and analysis on the topic

- Disinformation about migration (WMR 2022, Ch. 8)

- Migrants’ contributions (WMR 2020, Ch. 5)

- Inclusion and social cohesion (WMR 2020, Ch. 6)

Climate change and food insecurity

The IPCC defines climate change as “a change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Climate change may be due to natural internal processes or external forcings such as modulations of the solar cycles, volcanic eruptions and persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use. Note that the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in its Article 1, defines climate change as ‘a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods’. The UNFCCC thus makes a distinction between climate change attributable to human activities altering the atmospheric composition and climate variability attributable to natural causes”.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines “food insecurity” as a situation that exists when people lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development, and an active and healthy life. It may be caused by the unavailability of food, insufficient purchasing power, inappropriate distribution, or inadequate use of food at the household level. Food insecurity, poor conditions of health and sanitation and inappropriate care and feeding practices are the major causes of poor nutritional status. Food insecurity may be chronic, seasonal or transitory.

— Sources: FAO et al., 2013; IPCC, 2022

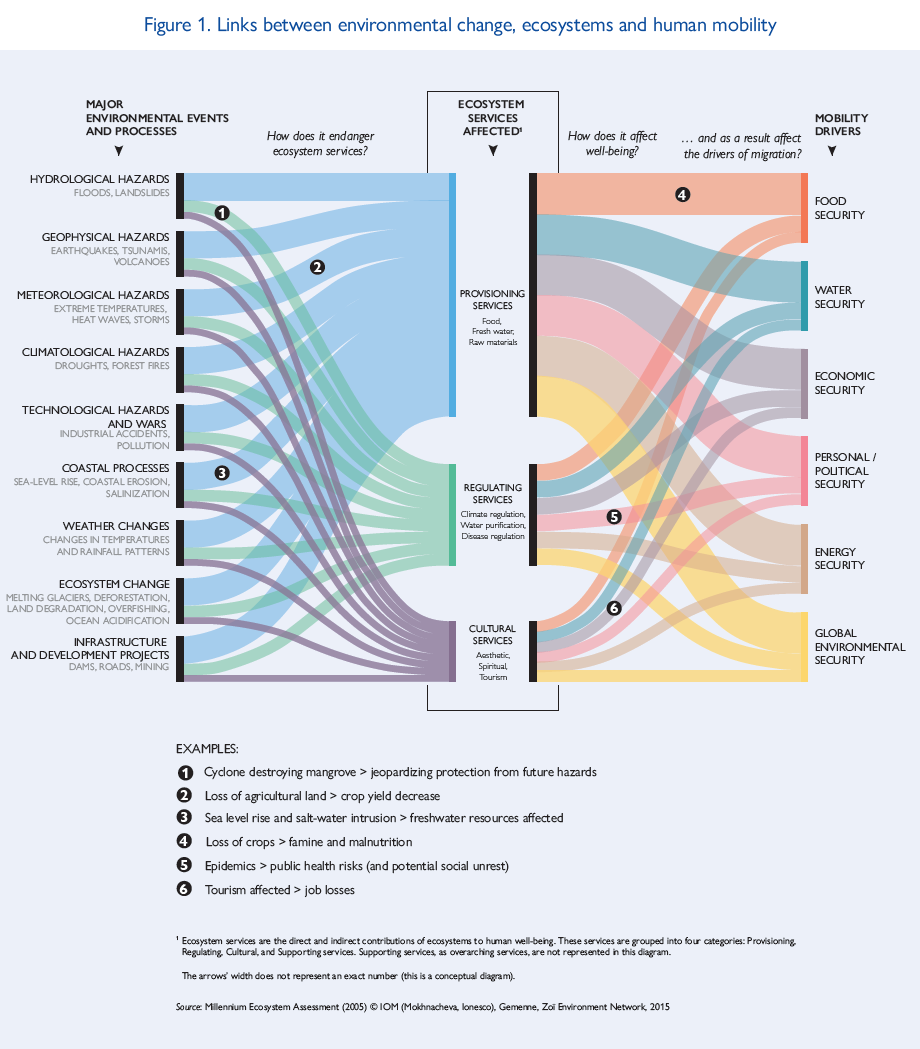

Environmental change and the multicausality of human mobility

Migration in the context of adverse climate impacts is mostly multicausal, as the decision to migrate is often shaped by a combination of different factors, including climate drivers. At the same time, a wide range of environmental and climate factors can influence the decision or necessity to migrate, from sudden-onset disasters such as typhoons and floods, to slow-onset processes like sea-level rise and land degradation.

The multicausality of climate change, food insecurity and human mobility, as well as the relationships between them, are very complex. Available evidence suggests that different levels of food security are related, at least partially, with the decision to migrate, and that they remain heavily shaped by gender and income levels.49 In some cases, food insecurity directly links climate disasters with the decision to migrate. However, food insecurity itself may be impacted by other factors, including social inequalities among affected communities, which shape individuals’ vulnerability and climate sensitivity levels. In the central dry zone of Myanmar, for instance, food insecurity and flood risks are a function of income, food production systems, transportation and access to water for irrigation, in addition to loss and damage from floods and droughts. In Chile, studies in the semi-arid region of Monte Patria highlighted that “uneven resource access, limited political bargaining power and the perceived impossibility to earn a sufficient income in the agricultural economy are locally considered as more important reasons for engaging in mobilities than considerations about climate change”; in particular, households and workers use preexisting labour migration channels to take themselves out of the municipality and towards the construction sector, to achieve higher education or to work in the mining industry.

The intersection of climate impacts, displacement and conflict dynamics in the Lake Chad Basin has been well documented. There, reduced access to resources, compounded by the impacts of climate change, have strong impacts on livelihoods and food security, creating conditions for conflict and driving mobility. But climate change— migration—conflict dynamics are highly contextual: in Ghana, for instance, non-climatic and ecological conditions reinforce potential climate-induced conflicts, triggering migration and farmer—herder conflicts. And in Colombia, Myanmar and the United Republic of Tanzania, migration appears to be driven by structural vulnerabilities in areas with low resilience, and food security emerges “as a product of environmental changes (droughts and floods), [and] as a mediating factor detonating violent conflict and migration in vulnerable populations”. Thus the multicausality of mobility is prompted by many factors and can take on many forms, with people moving near or far, internally or across borders, for a limited period of time or permanently.

Links between environmental change, ecosystems and human mobility

Immobility, poverty, and climate change

Climate change does not inevitably lead to the increased mobility of affected populations. In different scenarios, climate hazards can result instead in increased immobility, with distinct socioeconomic implications. In a region of Guatemala, for instance, a study found “no correlation between migration to the US and severe food insecurity in households, but the correlation became significant if the level of food insecurity was moderate, suggesting that families in extreme hardship did not have the resources to migrate.” In many settings, immobility is driven by multiple factors, including the availability of resources, gender dynamics and place attachment, in a continuum ranging from “people who are financially or physically unable to move away from hazards (i.e. involuntary immobility) to people who choose not to move (i.e. voluntary immobility) because of strong attachments to place, culture, and people”.

Looking at international movements, future projections suggest that climate change can induce “decreases in emigration of lowest-income levels by over 10% in 2100 and by up to 35% for more pessimistic scenarios including catastrophic damages”. In Zambia, vulnerability to climate change acts for some groups as a barrier to migrate, as “poor districts are characterized by climate-related immobility”. Persistent poverty means that some families cannot bear the financial cost of migration, and therefore remain trapped in climate-vulnerable areas. In Bangladesh, residents of climate-vulnerable villages who would like to relocate from their current residence are sometimes unable to do so because of financial barriers, lack of access to information, lack of social networks and unavailability of working-age household members. In these circumstances, well-planned and supported climate mobility, including relocation, may enable increases in well-being and positive outcomes.

Migration, climate change, and lessons for policymaking**

Environmental change and extreme climate events may result in diverse migration outcomes: a continuum of voluntary to involuntary migration; short-term, circular, longer-term and permanent movements; internally or across borders; over short or long distances; migration of individuals, whole households and entire communities (planned relocation); and immobility of trapped populations. Considerations for policymaking are outlined below.

The choice to migrate in the context of climate change often involves complex decision-making and is shaped by multiple ocioeconomic and environmental factors.

Climate change affects more directly the lives and livelihoods of those who depend on local natural resources for their livelihoods and security (e.g. farmers, herders, fishers and indigenous peoples).

Migration in the context of climate change impacts can be difficult to distinguish from other types of movements (e.g. labour migration, shorter-term circulation).

Migration in the context of climate change often results in differentiated impacts for women, boys and girls, and the elderly, linked to a number of factors such as family separation, disempowerment and increased dependency on other household members.

Slow-onset events and processes occur in some contexts with situations of intercommunal tensions and conflict. Their combined impacts can lead to population movements, which in turn further exacerbate environmental degradation and conflicts.

Urban areas are often the main destinations for people moving in the context of climate change. However, these urban areas can become hotspots of risk.

Reflection questions

What are some major environmental and climate events and processes that drive human mobility?

Based on the text, provide some examples of multicausal mobility.

In your own words, describe how social inequalities exacerbate individuals’ vulnerability and sensitivity to climate change.