Digital technology and migration

Below is a blog titled ‘AI in migration is fuelling global inequality: How can we bridge the gap?’ by Dr. Marie McAuliffe published by the World Economic Forum. Read it and answer the questions below.

AI in migration is fuelling global inequality: How can we bridge the gap

Artificial intelligence (AI) in migration and mobility systems has recently become a hot topic in research and policy circles, given the heightened prominence of the technology.

But as AI deployment rapidly advances through different policy domains, you might be surprised to learn that AI in migration has been present for several decades. This fact, together with major, long-term trends in international migration, points to the risk that AI technologies in migration and mobility systems are on track to exacerbate digital divides both between and within states.

AI early adopters

AI usage for migration and mobility management was, for some countries, a logical consideration in the 1990s, given the significant, sustained increases in international air travel, the deployment of online visa application systems and growing international border crossing data capture. The use of AI centred on managing increasing volumes efficiently and enabling enhanced data capture for strategic analytics.

But of course, those countries had existing advanced data systems and the resources needed to build on existing administrative data collection toward more elaborate AI-supported systems.

Immigration authorities in Australia, Japan, the United States, many European countries and Hong Kong, China initially sought to streamline processing systems using machine learning and other technologies. The immigration department in Hong Kong, for example, built its AI e-Brain system to process applications and build procedural knowledge through machine learning, reducing the need for case officer handling and faster processing.

The prerequisite to AI uptake is information and communications technology (ICT) digital capability, particularly the digital data capture of processes and applicants’ identity data. These require access to ICT infrastructure, electricity and ICT-skilled staff, whereas many countries worldwide lack these critical necessities, especially least-developed countries (LDCs).

These access issues further widen the gap between states, adding to the digital divide and the structural disadvantage experienced by LDCs in migration management. And the “asymmetry of power” in AI for migration globally is an ongoing problem.

Digital accessibility

It is not just inequality between states that will impact migrants. The move toward greater digitalization of migration management and increased use of AI, including for visa services, border processing and identity management, will increasingly require potential migrants to be able to engage with authorities via digital channels.

There are also calls for supporting migrants with digital access once they have arrived in a destination country and are required to navigate digital service channels for integration support. But first, potential migrants must be able to access entry-related digital processes. And this poses obstacles for many people around the world.

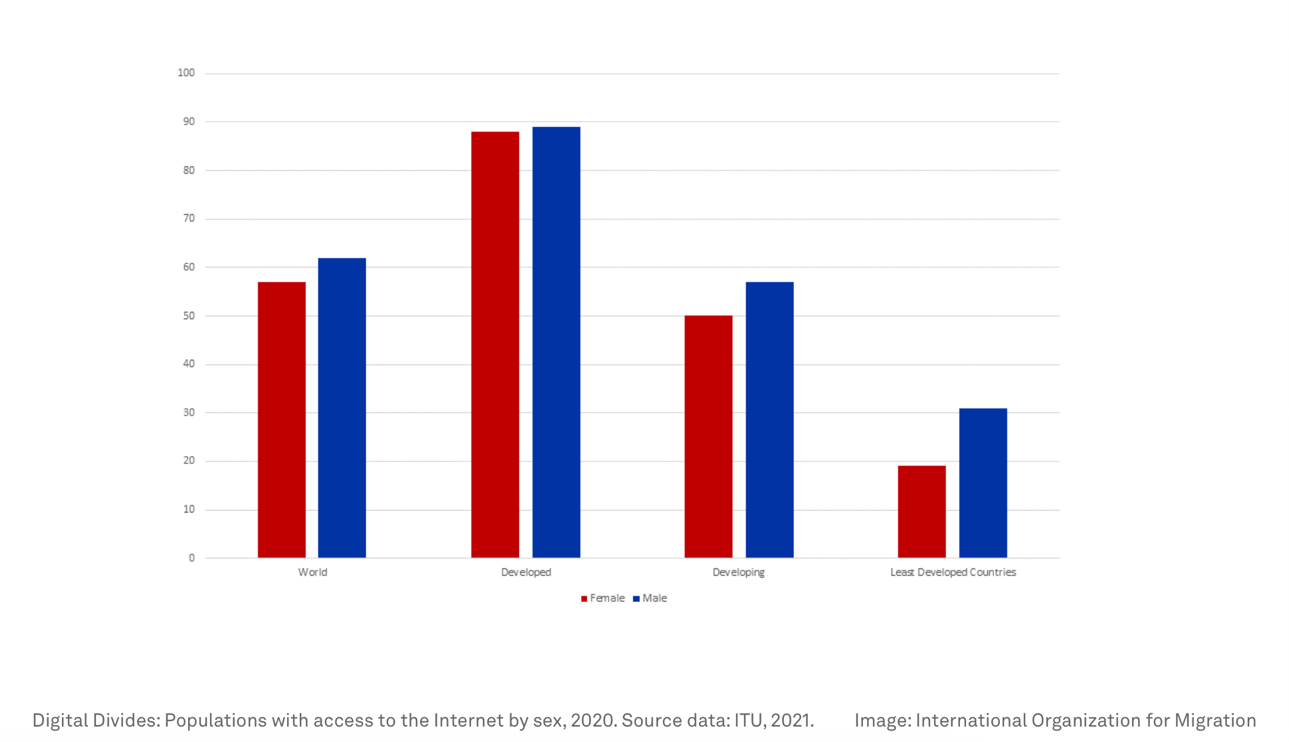

Access to digital platforms varies significantly within countries in some parts of the world. Data on internet access by sex and country development status, for example, show that females have much lower rates of access compared with males in developing countries and LDCs.

Source: McAuliffe, 2023

Notwithstanding important human rights concerns, digitalization can benefit migrants and states by reducing human error and speeding up processing. However, many people will be completely locked out of such processes, especially women from developing countries.

This exclusion is very concerning given long-term trends, which show that over the last 25 years, we have witnessed growing mobility inequality, with people from developing countries increasingly unable to access international mobility pathways.

Narrowing the gap

Analysis shows that most international migration activity is now taking place between wealthy countries as both origin and destination, with policy and resource impediments preventing global mobility from poorer countries.

We can also see a growing gender gap in international migration has really taken hold in recent years, with the male growth in international migrants now outstripping female growth significantly. For example, in 2000, there was almost gender parity among international migrants, with males accounting for 50.6% and females 49.4%; by 2020, the gap had grown significantly to 52.1% male and 47.9% as the result of long-term systemic change.

The expansion of digital technologies and their application in AI-supported migration systems in wealthy, highly-developed countries will further exacerbate the growing digital and mobility divides between and within states unless effective action to support developing country populations and authorities is developed and rolled out.

There have also been UN calls for tech development and investment in LDCs that would provide a way forward for tackling and stemming the growing global digital divides. That means not just concentrating efforts at the governmental level but also supporting communities to gain access to digital technology, including women in developing country contexts.

The benefits to migrants of faster, better technologies (including AI) to underpin migration are evident. But, how this is done is critically important from equality and human rights perspectives. That includes ensuring these technologies don’t inadvertently lock out communities and put further pressure on them and the authorities. Such a consideration is especially important when the international community is committed to advancing the Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

Supporting access to safe, orderly and regular migration requires active support for digital equality. Moving forward, we must recognize and support ICT access expansion with a clear eye on rising mobility inequality negatively impacting our migration futures.

Questions

What is the global digital divide?

Describe the advantages and disadvantages of AI usage for migration and mobility management?

How is digital technology and AI exacerbating inequalities within and between states?

Read more in the World Migration Report 2024 Chapter 9 “A Post-Pandemic Rebound? Migration and Mobility Globally after COVID-19” p. 256

The digitalisation of remittances during COVID-19

The World Bank predicted that global remittance figures would decline by 20 per cent due to COVID-19 in April 2020, revised to 14 per cent in October 2020, in comparison to pre-pandemic levels. However, remittance flows ended up declining by just 2.4 per cent globally, with USD 540 billion going to low- and middle-income countries in 2020, just 1.6 per cent below 2019 levels. In 2021, remittance flows grew by 7.3 per cent to reach USD 589 billion.

After controlling for economic activity and other pandemic measures, remittances responded positively to COVID-19 infection rates in migrant countries. In short, migrants seem to send more money to support their family when the COVID-19 infection rate goes up, which functioned as an automatic stabilizer for the home country (in terms of their output and consumption). This phenomenon stands in opposition to the World Bank’s prediction of a pandemic-induced decrease in remittances, but is consistent with the Bank’s long-term observations that remittances are counter-cyclical: when other economic indicators go down, migrants send more money, to help their struggling families and communities at home. In addition, studies have established a long-term relationship between remittances and real GDP, wherein a 10 per cent increase in remittances was associated with 0.66 per cent permanent increase in GDP.

Some analysts point out that the increase in remittances could also reflect the switch in the mode of sending remittances from informal channels to formal channels that was induced by pandemic restrictions. Prior to the pandemic, evidence suggests that significant proportions of remittances were being transferred to families through informal channels (such as hawala or hundi or fei-chien networks, or in person). However, with lockdown measures, greater digitalization and reduced remittance transfer fees, migrants have undergone a behavioural switch, and have started relying more on formal channels to remit their transfers, as shown in the text below.

African money transfer firms thrive as pandemic spurs online remittances

Having fled an economic implosion in his native Zimbabwe, Brighton Takawira was able to support his mother back home with modest earnings from a small perfume business he set up in South Africa.

Then the pandemic struck. Borders closed. The buses he had used to send his cash stopped running. The pandemic gave remittance companies an advantage over their main competition in Africa: the sprawling informal networks of traders, bus drivers and travellers used by many migrants to send money home.

“I had to send something, even a few dollars”, said Takawira, though it meant sometimes going without bread. So he tried out an online remittance company on a friend’s recommendation.

He is one of many African migrants being pushed towards digital transfer services, often for the first time, during the pandemic.

This is fuelling a boom for Africa-focused money transfer companies, despite predictions from the World Bank of a historic 20% drop to \$445 billion in remittances to poorer countries this year due to a pandemic-induced global economic slump.

“We saw an increase of transfers as the diaspora wanted to help their family”, said Patrick Roussel, who heads mobile financial services for the Middle East and Africa at French telecom company Orange — a dominant player in French-speaking Africa. “We’ve seen an influx of new customers, and we see them mainly coming to us from the informal market”, said Andy Jury, chief executive of Mukuru, the company Takawira now uses.

Like Takawira, many had to dip into savings or make other sacrifices to do so, analysts and company officials say.

Jury and other industry executives say that shift is likely to last as digital remittance services are typically cheaper, faster and safer than informal networks, which are difficult for governments to regulate. Mukuru, which focuses mainly on African remittances and allows customers to send both cash and groceries, has seen a roughly 75% acceleration in growth compared to last year.

Remittances to sub-Saharan Africa officially totalled \$48 billion last year, according to the World Bank. Experts, however, say that figure tells only part of the story. Much of the money Africans ship home via informal networks is absent from official data. As those networks ground to a halt during lockdowns, formal money transfer businesses — particularly digital platforms — were suddenly the only game in town.

Source: Abridged extract from Bavier and Dzirutwe, 2020.

Questions

According to the World Bank, how are remittances impacted by global crises?

How did COVID-19 impact the mode of sending remittances?

Describe some benefits of digital remittance services.