Youth and Migration

Definition of youth

There is no single universally accepted definition of “youth” and definitions vary across countries and organizations (See Table 1). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines \“youth\” as individuals aged between 15 and 19 years. The African Youth Charter has a broader age range and its definition encompasses individuals between 15 and 35 years old. Kenya uses the 15-34 year age bracket while an organization such as the Islamic Development Bank uses 15-35 years. For the purposes of this module, we will use the United Nations definition, which classifies \“youth\” as individuals aged between 15 and 24 years.

Did you know? International Youth Day is celebrated on 12th August

Youth migration

International migration provides the chance for many young individuals to improve their lives, including through international education, training and work. Youth migration also brings significant benefits to both countries of origin and destination. However, youth migration today is also taking place amidst challenging circumstances, such as increased misinformation and disinformation about migration, political polarization, elevated levels of unemployment and underemployment in some economies, climate change concerns, social exclusion, gender inequality, among others.

Why young people migrate

Young people migrate for a wide variety of reasons. A key driver of youth migration is the search for economic opportunities. This is unsurprising, as people aged between 15 and 24 — especially in low- and middle-income countries — can face significant challenges in securing decent work. The unemployment rate of youth globally in 2022 was three times higher than that of adults aged 25 or above. Further, in 2022, an estimated 23.5 per cent or 289 million youth were not in education, employment or training (NEET), with young women twice as likely as men to be NEET (see breakdown of subregions in figure below). While seeking better economic opportunities remains a major driver of youth migration, it is important to recognize that the aspirations to migrate may differ depending on the level of development of the countries in which they live. Young people from less developed countries often seek economic stability and better living conditions abroad, while those from more developed countries often migrate for cultural enrichment, education or professional advancement.

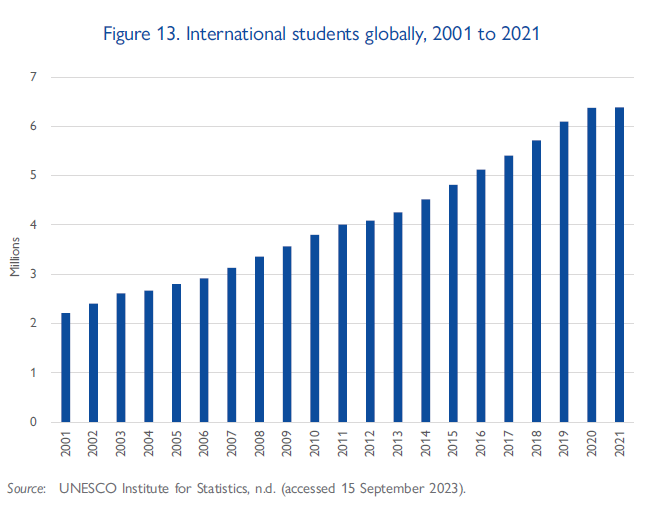

A large number of youth also migrate to pursue education and training, and higher education remains a major factor that drives youth migration. Recent data from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s Institute for Statistics (UNESCO) shows an increase in the number of international students in recent decades, rising from just over 2 million in 2001 to more than 6 million in 2021 (see section below on internationally mobile students).

Beyond moving for economic and educational opportunities, youth migration is also motivated by the search for personal freedom and can be a lifestyle choice or cultural process during key years of personal development, change and transition to adulthood. Marriage migration is also a notable feature of international youth migration, with a significant number of young women from developing countries — particularly in Asia — migrating with the intention of getting married. Despite the “social, cultural and demographic transformation of the communities of origin and destination” resulting from marriage migration, many young women often find themselves in patriarchal and restrictive situations in their new marriage households. Conversely, for some women, migration becomes a way to avoid an early marriage (see more here).

Conflict and violence also factor heavily in the decisions of some young people to migrate and significantly contribute to youth displacement. While it is widely acknowledged that millions of young people continue to be displaced both internally and across borders, exact figures are difficult to ascertain. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) global trends and statistics, for example, are not reported by youth age brackets. The invisibility of youth in displacement data also extends to internal displacement. Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) data are also not disaggregated by age. However, a 2020 IDMC report — upon “applying national-level demographic data to the number of IDPs per country” — estimated that in 2020, there were 10.5 million IDPs globally between 15 and 24 years, displaced due to conflict, violence or disasters.

International students

The number of internationally mobile students globally has significantly increased over the last two decades, as highlighted by data collected by UNESCO. In 2001, this number was at just over 2.2 million. A decade later, the number of internationally mobile students had grown to more than 3.8 million. This number continued to increase in the years following, rising to over 6 million in 2021, nearly triple the figure twenty years prior. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic and related mobility restrictions, the number of internationally mobile students remained strong (Figure 4). Between 2020 and 2021 — at the height of the pandemic — the number of internationally mobile students slightly increased (from 6.38 million to 6.39 million), defying expectations.

From WMR 2024, Ch. 2.

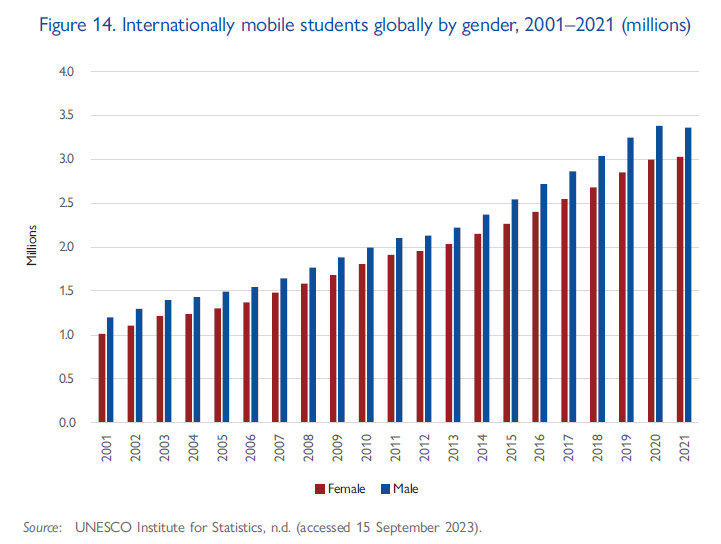

Historically, flows of internationally mobile students have been gendered, with male students consistently outnumbering female students. In 2001, there were around 1 million internationally mobile female students (45% of the total) and 1.2 million male students (54%). While this gap has narrowed over the last twenty years, the number of internationally mobile female students remains lower than that of male students (Figure 5). In 2021, around 3 million internationally mobile students were female (47%) and males comprised around 3.4 million (52%).

From WMR 2024, Ch. 2.

Data deficiencies

There are significant data gaps when it comes to youth migration and displacement, often limiting the comprehensive analysis of youth migration patterns and dynamics. Data on youth migration is often inconsistent and limited. For example, as Belmonte and McMahon (2019) observe, while migrant stock data from UN DESA show disaggregated data by age in destination countries, they do not provide this data for origin countries. Both UNHCR and IDMC data on refugees/asylum seekers and internally displaced persons are also not disaggregated by age.

Inconsistent data on youth migration is in part the result of the lack of a unified definition of “youth”, posing challenges when it comes to collecting data that is comparable across countries and regions. Different definitions “could also result in inaccurate data collection, leading to misunderstandings of the challenges that may be specific to young people.”

Key resources on the topic

Children and unsafe migration (WMR 2020, Ch. 8.)

Global Overview (WMR 2024, Ch. 2)

Defining and mapping youth migration (Belmonte and McMahon, MRS No. 59, 2019)

Definition of youth (United Nations, 2013a)

Youth and migration (United Nations, 2013b)

UNHCR youth report (UNHCR, 2023)

Internally displaced children, youth and education (IDMC, 2023)

Youth, migration and development report (Samuel Hall, 2022)

Youth, migration and development case studies (Samuel Hall, 2023)

Understanding return migration from the Gulf to East Africa during crisis: youth and gender dimensions (Kitimbo, 2024)

International Students data (UNESCO, n.d.)

Reflection questions

What are some of the key drivers of youth migration?

What are three challenges facing youth refugees from around the world? How do these specific challenges differ to those faced by older refugees?

Explain why collecting data on youth migrants is often challenging?