Gender and Migration

A growing global gender gap in migration

Research on women’s international migration from the 1980s noted the increasing presence of women migrating independently, especially as migrant workers, leading to the introduction of the concept of the feminization of migration. This notion was consequently elevated as a mantra in migration and gender research, one seldom questioned since the 1990s. However, a deeper examination of migration trends and patterns requires nuancing this view. Although global data sets do not provide information on migrants of diverse genders, as the collection of gender-disaggregated data remains uncommon, global sex-disaggregated data remain useful to better understand demographic trends from a gender binary perspective.

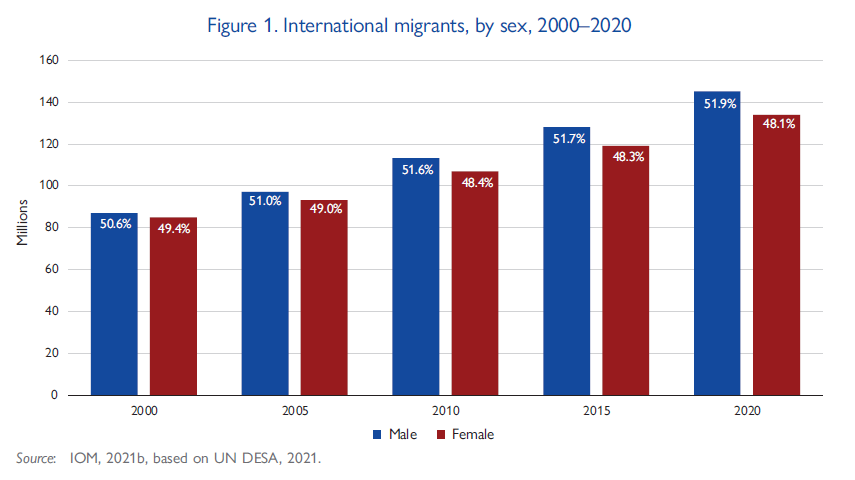

History attests that there was a steady increase in the number of international female migrants from 1990. However, evidence points to a growing gender gap globally over the past two decades. As highlighted in the previous world migration report (Figure 1 below), the share of female migrants has been decreasing since 2000, from 49.4 per cent to 48.1 per cent. The gap between female and male international migrants increased from 1.2 percentage points in 2000 to 3.8 percentage points in 2020.

Hence, though the number of female migrants has increased over the years, migration is not more feminized. On the contrary, it has become more masculinized when considering the share of female and male international migrants at the global level.

From WMR 2024, Ch. 6.

Gender influences all migration experiences

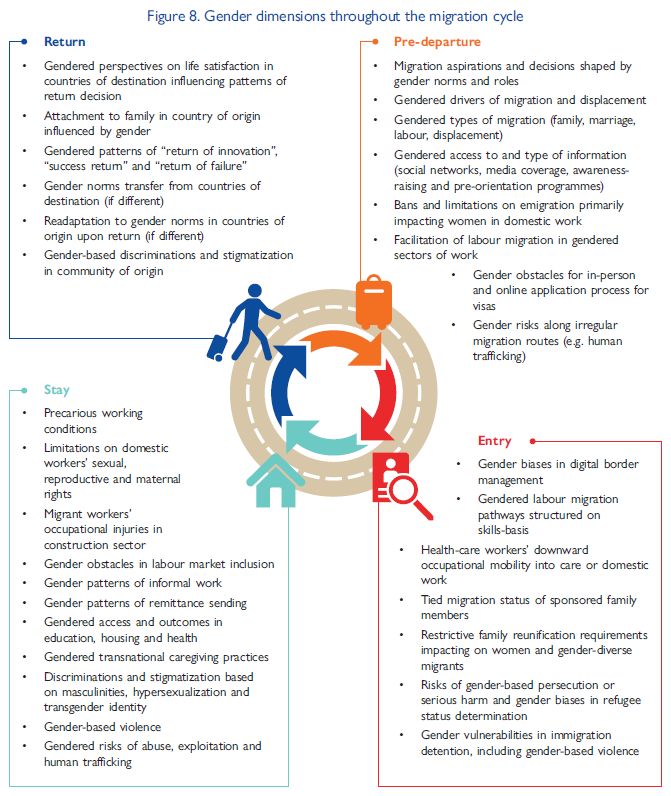

Gender norms and biases affect many aspects of day-to-day life. However, they take on a specific importance for migrants, influencing their migration experience to the extent that migration has been described as a gendered phenomenon. Alongside a range of other overlapping factors such as age, race, ethnicity, nationality, disability, health and socioeconomic status, gender impacts the different opportunities igrants may have and the various obstacles and risks they may face in pursuing them. By setting out different roles and expectations for migrants of specific genders, the social norms of countries of origin, transit and destination may influence, for instance, who can stay and migrate in a household, the motivations and options for migration, the preferred destination countries, the type and means of migration, the goal and objective of migration, the sector of employment or the disciplines studied, the status afforded by legislations of countries, including in terms of rights and benefits, and the list goes on. These gender dimensions of migration in turn impact societies in countries of origin, transit and destination. Similarly, in displacement contexts, gender considerations underpin individuals’ trajectories, experiences and protection, and even their very decision to flee when related to gender-based discrimination and violence that may, in some countries, lead to international protection, including refugee status.

The gender dimensions summarized in figure 8 below are approached through the prism of gender inequalities, highlighting how gender may trigger diverse opportunities, vulnerabilities and risks for migrants. This section should be understood as offering examples of the countless ways gender and migration interact, since it would be impossible to comprehensively cover all of these opportunities, vulnerabilities and risks.

From WMR 2024, Ch. 6.

Cross-cutting gender challenges

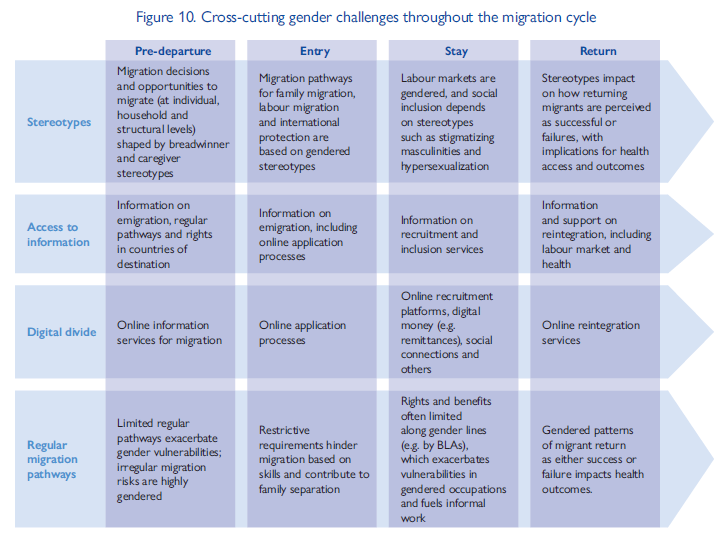

Exploring some key gender dimensions at each stage of the migration cycle highlights the extent to which migration is beset by gendered obstacles, challenges and vulnerabilities for men, women and gender-diverse individuals, often reflecting broader systemic gender inequalities. Four key challenges cutting across the whole migration cycle are identified below and highlighted in Figure 10. All relate to gender norms that more broadly underpin structural gender inequalities and require adopting and implementing gender equality policies and interventions, including education and awareness-raising. Each challenge is complemented by a promising practice or innovative intervention selected across a wide range of geographies. These most notably showcase the importance of a multi-stakeholder approach and of local initiatives and practices that often involve migrants of all genders or are designed in a gender-responsive manner, and that can be leveraged at the local, national, regional and global levels of migration governance.

From WMR 2024 Ch. 6.

Why is sex- and gender-disaggregated data in migration important?

Sex- and gender-disaggregated migration data are essential to inform evidence-based migration policy, programming, operations, and practices that capture the realities of all migrants. Sex-disaggregated dataincludes biological information often assigned at birth, determined by anatomy which includes male and female. Gender-disaggregated datarefers to the gender information an individual assigns to themselves, which may or may not correspond with their sex assigned at birth or the gender attributed to them by society. Recognizing the sex and gender dimensions of migration through evidence-based research and in disaggregated datasets can help to address gender-based discrimination and pre-existing systemic inequalities.

Key resources on the topic

Global Overview (WMR 2022, Ch. 2)

Regional developments (WMR 2022, Ch. 3)

Global Overview (WMR 2024, Ch. 2)

Regional developments (WMR 2024, Ch. 3)

Gender and migration (WMR 2024, Ch. 6)

Gender and Migration Data (G. Abel, 2022)

Women & Girls on the Move Issue 2 (IOM, 2023)

Impacts of COVID-19 on migrants and migration from a gender perspective (IOM, 2022)

The Research Handbook on Migration, Gender and COVID-19 (edited by Marie McAuliffe and Céline Bauloz, 2024)

Reflection questions

What are some examples of how gender impacts the experiences migrants?

What was the gap in percentage points between male and female migrants in 2020? How has this changed over the last two decades?

What are two critical reasons we need sex- and gender-disaggregated data in migration?